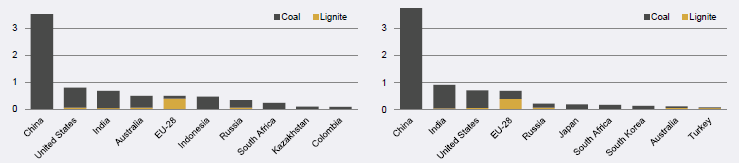

In the energy World everybody knows that, when it comes to coal, no one beats China – which triples the production volume of the 2nd country in the list, the U.S. But being the biggest is not without its problems.

Figure 1. Coal production (left) and consumption (right) by country in thousands of millions of tons (Source: IEA, 2016)

And China is now facing one which it wants to solve by imposing severe import restrictions to this commodity. Given their sheer market-share, it’s clear this will influence the global market. Let’s dive into it.

A little background

The story begins in 2015. Back then, threats of massive coal bond defaults threatened China’s financial sector (you can read more on the issues of Winsway, Sichuan or ChinaCoal). Also, it has constantly been more favourable for Chinese buyers to buy seaborne imported coal rather than domestic coal, since the latter needs to be transported to the southern industrial regions from the north. Investment in rail infrastructure from the north to south has improved this issue, but never really solved it.

So, in a great political sleight-of-hand, Beijing seized yet another opportunity to reform the country’s heavy industry under the pretext (or disguise?) of cutting back on their own domestic production of low-grade materials and improve their environment.

What followed was a massive intervention in domestic coal production, initiated in mid-2016, where the Government restricted working days at coal mines. This worked, but also drove a sharp rise in domestic coal prices, which rose from 390 CNY/t (60 USD/t) in mid-2016 to well over 600 CNY/t (87 USD/t) in 6 months.

This brought a breath of fresh air to the dying industry of Coal. Loss-making mines returned to being profitable, as this resulted in a situation where China looked to import higher-grade materials, boosting the prices of these commodities worldwide.

On the problem

But this Bull Run was not expected, so the working day restriction was removed, although the core of the policy remained in place and much of the capacity that was taken down remained down. Nevertheless, the side-effect was already there: China’s utilities firms began having financial problems.

Take Huaneng Power International (or HNP for their closest friends) for example. The stock-traded arm of China’s largest power producer, in the end of last year, just posted its worst quarterly net loss since the 2008 financial crisis. Also, Chinese media have been reporting on disagreements between power generators and sellers for a while now, culminating this January with the news that the four biggest coal generators had sent an urgent letter to Beijing warning that many plants nationwide were running out of cash to buy coal and that banks were curbing lending (more information here and here).

So now, instead of having financial problems in its coal mines, China just added the prospect of an ever increasing debt also in its utility sector, which it responds by merging one of the largest utilities companies (China Guodian Corporation) with the state owned coal company (Shenhua Group Co., Ltd.), to form a behemoth called China Energy Investment Corp LLC.

But at least its internal coal production was rising again, which was helping to regulate prices, and Beijing began (slightly) backing off the coal sector (ergo going back on its promises of going evergreen) and it even approved five large-scale new coal mines since January. And so, in that 1st quarter of the current year, coal output grew to 804.5 million tonnes (over 3.9% YoY).

Nevertheless, China’s coal production in March fell to 290 million tonnes, according to data from the National Statistics Bureau. Although this is still 1.3% higher than last March (YoY), it’s the lowest since October. One may say that it’s not unusual for prices to fall after peak winter demand, and it would be correct, if it weren’t for the price rollercoaster that came with it and that ended with domestic coal prices down about 20% from the records hit in January – a clear sign of oversupply.

China’s largest coal producer China Shenhua Energy lowered its sales and production forecasts recently, reducing its production in 1.8% from a year ago and expecting sales to decrease by as much as 3%. So, if the PRC doesn’t want its coal companies defaulting again, domestic prices will have to rise without losing competitive advantage against Indonesia and Australia.

The Chinese Solution

To counter the problem of oversupply, quench the thirst for cheaper imported coal from Australia and Indonesia and support domestic coal production, Beijing has done what they always do: regulate again.

In an apparent reminiscence of the 19th century Nanjing Treaty “Open Ports” scheme, ports in the country can be considered as divided into two classes according to their degree of openness: a Class I port for instance, allows foreign goods and people to enter and leave its territory, while a Class II port allows only Chinese nationals and goods, as well as bilateral personnel from neighbouring countries.

So, to achieve its goals, the state imposed trading and port restrictions on foreign coal on Southern and Eastern Class I (and even Class II) harbours. This means that traders will no longer be able to build higher port stocks to resell, but instead are forced to find end buyers to take out arriving cargoes. Nevertheless, even end-users will have to trade on a ship-by-ship basis and face tightening inspections and customs clearances. Many power generators for instance are filling appeals with the aim of at least getting permission to execute existing contracts with foreigners.

In summary, the Chinese created another confusing situation, fuelling more uncertainty into the market, with many vessels not being allowed to dock in main harbours. Since the weekend of April 15, thermal and coking coal imports at ports in Eastern China, such as Fangcheng and Zhoushan, are now restricted, while in the Southern Coast, port authorities in the Fujian Province (where the port of Xiamen is located) are telling steel mills that, in their case, this would extend to a full-scale unloading ban.

According to some sources, this state of affairs will last until the Chinese thermal coal prices stabilize which, according to some analysts, means at least 6 months, although monthly reviews of the situation (and the corresponding restriction adjustments) were promised.

The effects in the region

At the time of this article, China’s seaborne coal imports had slumped to 3.45 million tonnes (in the week ended April 21), down 30% from the weekly average of this year so far.

Certainly, news of the restrictions boosted domestic prices, with benchmark thermal coal futures on the ZCE jumping almost 3% on the 16th of April, closing at 570.2 CNY/t (or 90.7 USD/t), which was the biggest gain since August last year. Although domestic price control by Beijing isn’t “official”, it’s widely believed in the industry that a range anchored around 550 CNY/t (around 88 USD/t) is a level that the government believes balances the needs of utilities and mining companies. Also, unless something changes, that is a price level that makes domestic coal competitive (once the duties and other import taxes are taken into account).

So, domestically, the goal is not so much to manage price but, probably, to reduce imports to 2017 levels. Therefore, I believe one should expect coal imports to gradually reduce in the coming months, as all players know that a drop in imports in this shoulder season between winter and summer isn’t much of a problem to exporters.

The problems will arise if there’s a sustained downturn. And this is a scenario that, I believe, can happen. Even if China’s exports were to slow (as a result of this policy), it has the financial muscle to support its industries by fuelling internal growth through more infrastructure investment, both in China and in other countries (remember the new “silk-road” Initiative).

The effects on the API2

Although having very large reserves of coal, for many years the EU has been a net importer of this commodity, mainly from Russia, Colombia, United States, South Africa and Australia. Also, even though domestic production is falling rapidly, heavy industry in the EU still relies heavily on the use of coke.

Even if our main sources of imports (Atlantic Region) do not overlap directly with the Asia-Pacific region, when there are problems with their main suppliers, particularly Indonesia and Australia, China turns to other sources. And we also have to factor in the freighting, which affect the balance of supply and demand, by focusing in specific regions in times of high-demand. This means that coal prices worldwide tend to be highly correlated in the majority of cases.

Figure 4. Example of past 5y price correlation of McCloskey Coal FOB Price Indexes for several origins

And so we focus on derivatives contracts to ensure a good risk management within the market, and our benchmark is the API2 Index. This is the primary price reference for physical and over-the-counter (OTC) coal contracts in northwest Europe, acting as a proxy for CIF (Cost, Insurance and Freight) prices of coal delivered to the ARA region (Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp).

Although API2 futures contracts opened on Monday with gains, they’ve since corrected downwards. It’s all pretty fresh right now, and only time will tell for how long will these restrictions remain in place, how will companies honour previous commitments, how solvent will China’s domestic mining companies be after it and how will exporters react. Nevertheless, if China reduces significantly its level of imports, we may see a more competitive market for coal.

Hugo Martins |Analyst

If you found it interesting, please share it!

Recent Articles