An energy transition based on confusing legislation and high European targets.

How is the country moving towards respecting the PNIEC objectives? Great intentions and still few measures, definitely a great challenge and a race against time.

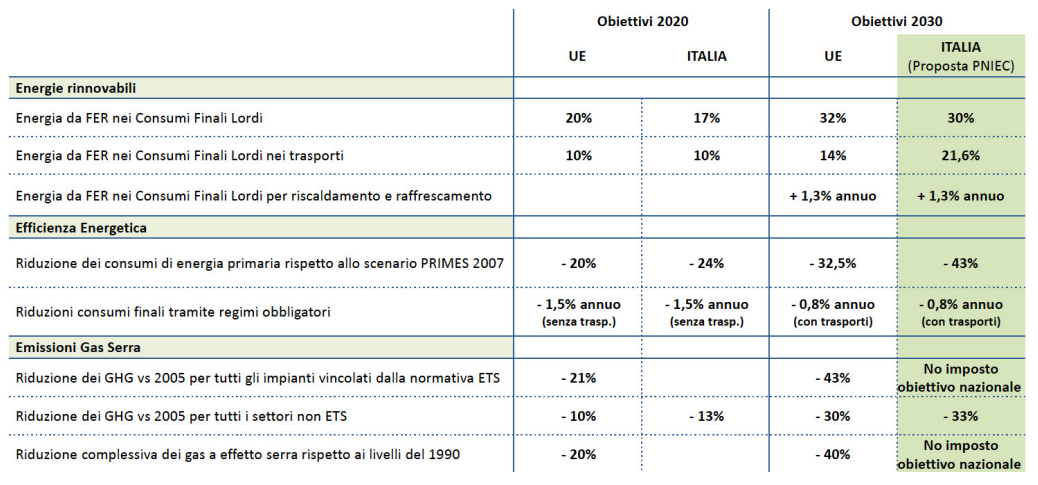

Renewable energy, such as wind and solar, is now accepted as reliable and highly cost competitive in markets all over the world, driving its rapid global growth. Many large corporate electricity customers see great benefits, both economic and related to their brand reputation and sustainability, in switching to renewable energy. 2017, indeed, saw a new record set for clean energy purchased by corporations worldwide, a record that was broken in 2018. But more is required to meet emissions targets. Concerning Europe, the Winter Package set high standards in terms of targets: 40% reduction in GHG emissions with respect to 1990 levels, 32% renewable energy share and 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency.

But how is Europe going to succeed in these objectives? Through the PNIEC, each country has set its targets, implementing its own regulation toward the achievement of a greener energy sector. However, many countries do not face a defined normative and this is the reason why these targets seem unlikely to reached.

Today, we are talking about how Italy is managing the tremendous changes that its energy sector has to face, respecting the European Commission orders. As we discussed in our previous article, the PNIEC objectives for Italy are very ambitious. Bruxelles itself finds hard to achieve targets without a mature legal framework. It is well known that the energy transition period for reaching these objectives is 2021-2030 and regulation in Italy is still too complex and uncertain. Moreover, the country results to move slowly towards renewables and new energy mechanisms, such as PPA, self-consumption and demand aggregator, respect to the rest of European countries. It represents a real race against time: will be Italy fast enough to implement its energy transition?

Let’s analyse how Italy is currently dealing with the key tools expressed in the Winter Package in order to help renewables entering in the European countries’ energy sector. Before entering into details, I can anticipate you that the path seems hard and long.

Figure 1: PNIEC objectives for Italy vs Europe

PPAs

If in the USA, Latin America and, recently, the Nordic countries found in PPAs a valuable tool in financing the energy transition to date, in the South European markets these tools are making more noise than real projects implementations, as it is currently happening in Italy.

This is why PPAs are one of the key points toward the energy transition in Italy. In fact, removing barriers to the development of PPAs in Italy is one of the objectives of the “Ministerial Decree on the promotion of the production of electricity from renewable sources”, better known as the Decreto FER, approved the 10th August 2019.

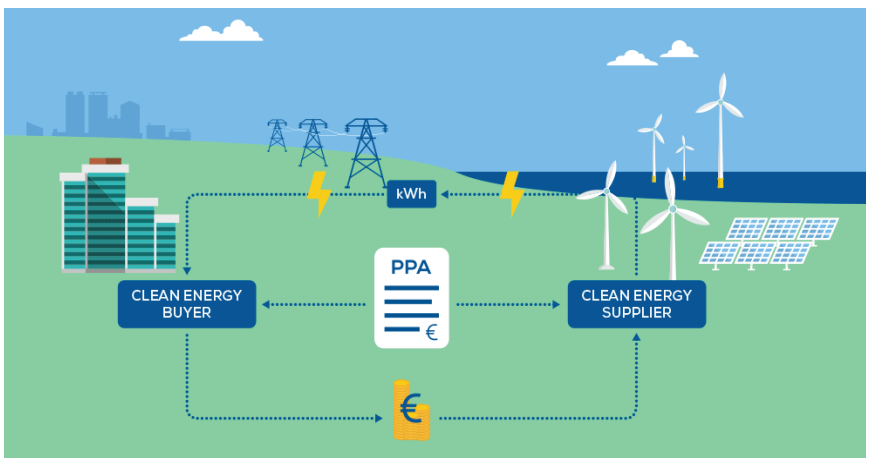

But let’s take a step back: with PPAs, we are talking about a long-term contract between a generation resource and a corporate customer that defines a price structure and volume of energy to be supplied over a fixed period. As declared by the company DNV GL, a well-structured PPA is a win-win deal, ensuring a steady stream of income for suppliers and providing price security and visibility that simplifies business planning for the buyer. It is also seen as a potential tool to encourage solar and wind sectors development.

Figure 2: PPA structure (Solare B2B: PPA verso un futuro multitecnologico)

As we were discussing, the DECRETO FER is document with a first approach towards PPAs. It states indeed that, once approved, it will be necessary to create a platform for long term energy negotiations and trading. Last modifications, in particular, ask to the Italian System Operator (GSE) to make available on its website the main characteristics of the projects promoting meeting for the PPAs interested parties.

An additional incentive on the PPAs development in Italy comes from the definitive text of the Renewable Directive for the period 2021-2030 presented to Bruxelles the past December (Winter Package). The document contains indications on PPAs’ future and energy communities that from 2021 will not be prohibited within the European Union. The Policy Officer of the European Commission, Francesco Maria Graziani, confirms these statements and declares to the Solar B2B journal that the members of these energy communities will keep their rights as consumers: the communities will have an own real juridical autonomy. So, from 2021 for sure there will be a clear regulation for PPAs.

Last year, PPAs were starting to shyly move the first steps in Italy. However, the fact that these tools could make safe incomes just on long-term periods makes more difficult the effective entering of PPAs in the market. In Italy, only few consumers are willing to stipulate contracts longer than 2-3 years, while the real strength of PPAs it is in the contrary the long-term period, between 5 and 10 years.

Although the country is slowly travelling towards this new concept, there are some virtuous consumers which started to believe in this non incentivised tool from the very beginning, particularly in the photovoltaic ones:

- 10 MW installation in the Milan area (in progress) for a joint venture between the supplier A2A Rinnovabili and Fondazione Fiera Milano;

- 100 MW installation in Cagliari province for a 5 years contract with EGO Trade;

- 17 MW installation in the Sicily region for a 10 years contract between Canadian Solar, Manni Energy and Trailstone;

- 20 MW installation in the Basilicata Region for a 10 years contract with Audax Renovables.

Self-consumption

As for PPAs, the Renewable Directive also studies the case of self-consumption, defining it a key point for the increasing objective of energy efficiency and renewable energy share within the European members (articles 21 and 22).

In Italy, it is completely missing a legal framework for the development of collective energy production and consumption, which is clearly stated in the directive fundamental points. In the country it is possible to produce, store and sell energy just with one to one mode. For example, a jointly owned building can`t use electricity produced from a PV installation located on its rooftop.

According to the PNIEC objectives, self-consumption evolution is a priority, moving from 400 MW installed in 2018 to 2.000 MW for 2021-2025.

In terms of incentives, the Legge di Bilancio 2019 prorogues until the 31st of December the bonus for the installation of domestic photovoltaic plants up to 20 kW. The tax deduction is around 50% up to a maximum expense of 96,000 euros per property unit and is divided into 10 equal annual instalments.

Concerning photovoltaic installation higher than 20 kW, the DECRETO FER establishes some competitive downward procedures from basic rates. The installations are subjected to registration in special registers if they are plants under 1 MW, while subjected to participation in special auctions if they are plants above 1 MW.

Demand aggregator

In September, Terna (National Electric Grid) started a pilot project for the participation of mixed enabled virtual units (UVAMs) in the market for dispatching services (ancillary services). UVAMs are an aggregation mode characterised by production, storage and consumption units, with the aim of reducing energy costs.

With ancillary services we mean the operations that consist in the modification of the energy exchange (active and reactive) between plants and grid, with the main objective of guarantee stability in terms of frequency and voltage. This type of service has been always implemented by thermoelectric and hydroelectric plants, with capacity higher than 10 MW, able to be easily and fast modulated in power. This service is starting to become more and more difficult, since the number of thermoelectric installations is decreasing, while renewable energy plants are definitely increasing. Reducing the minimum capacity to participate in balancing services may be the appropriate solution, so that renewables can start entering in the market, including storage devices. The figure of the aggregator has the main objective of bringing together a certain number of distributed resources offering the related services to the network operator in a unified manner.

This major project is what Terna is trying to develop with UVAMs, with an inferior limit power control of 1 MW. However, within an aggregation, units of capacity from 55 kW can also participate. The service offered can be bidirectional, but also only monodirectional (power increasing or decreasing).

However, within the 1.000 MW available for these units, just 350 MW have been assigned, making this service still in a preliminary phase.

The figure of the demand aggregator is clearly stated in the European Union Winter Package, as the self-consumption, as the PPas. Italy knows that these tools are the keys for more participation of renewables in the energy sector and, therefore, for the fulfilment of the PNIEC targets. These instruments are still pilots, but what is clear is that at least Italians understand that things have to make the next move.

If you found it interesting, please share it!

Recent Articles